Задумка Константина Чайкина, подарившая жизнь наручным часам под названием Cinema, зародилась ровно 10 лет назад: в апреле 2012 года.

В год первого круглого юбилея рассказываем, как идея оформилась в единственное в своём роде хронометрическое изделие, олицетворяющее все те фильмы, что мы смотрим на экранах наших телевизоров и девайсов. В наручных часах премиального сегмента важно не только филигранное исполнение, но и стоящая за ними идея. Богатством и ювелирным качеством отделки искушенных поклонников Высокого часового искусства поразить довольно непросто. Уж сколько шедевров они повидали на своём веку! Другое дело – изделие с уникальной историей и модулем, построенным по её мотивам. Часы Cinema Константин Чайкин придумал в 2012-м – и запатентовал изобретение год спустя.

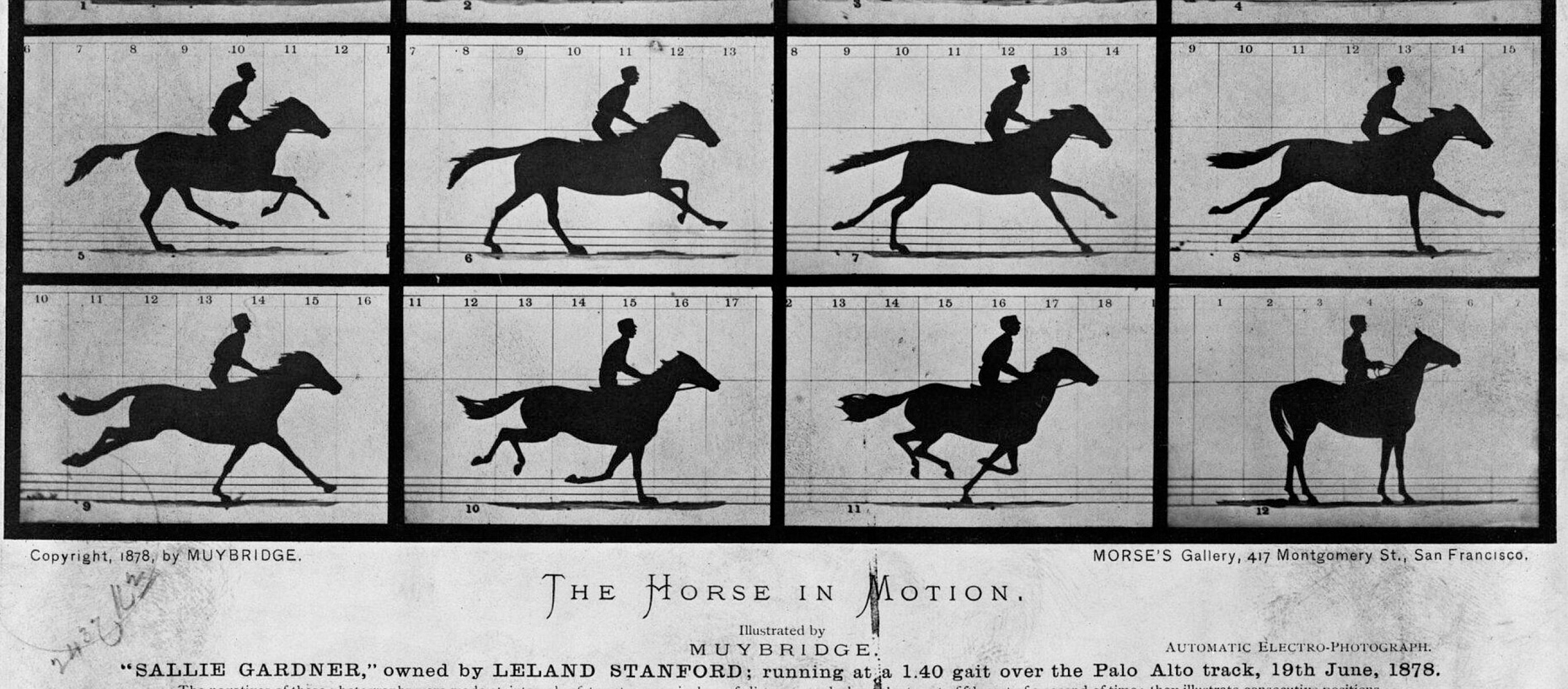

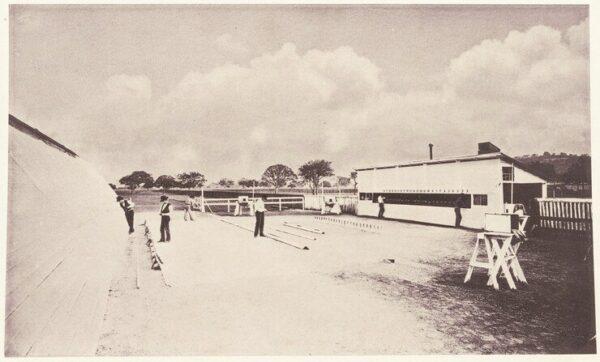

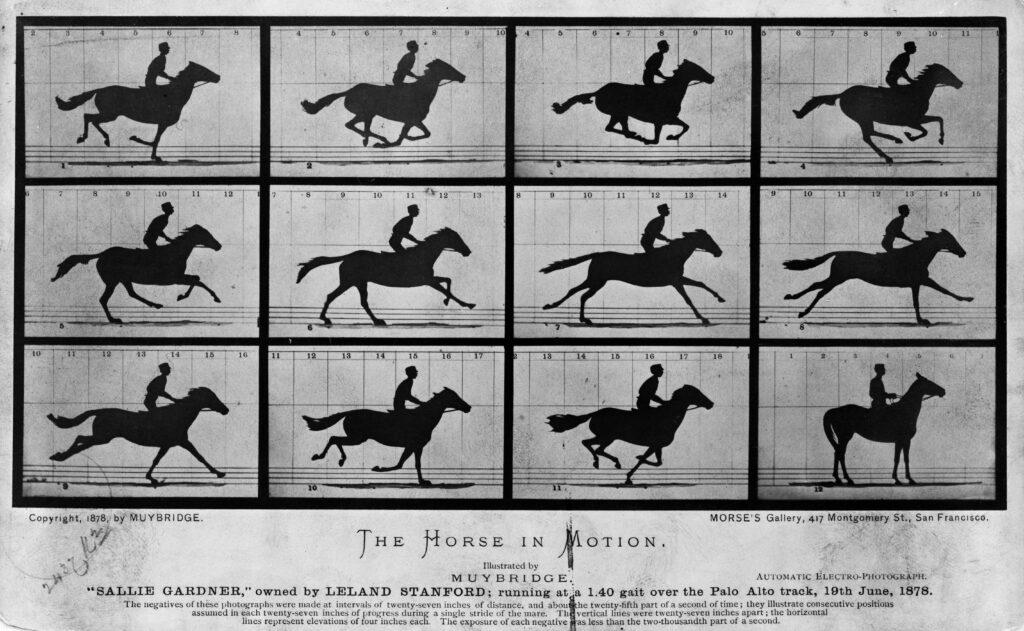

Любопытно, что в данном случае мы знаем даже точную дату, когда мысль о таком устройстве пришла автору в голову: 9 апреля. В этот день Константин открыл «Гугл» и обратил внимание на гугл-дудл дня: «галопирующую лошадь Мейбриджа». Что же произошло 9 апреля? В этот день родился Эдвард Мейбридж, придумавший и сконструировавший зоопраксископ. Термин состоит из нескольких частей: в переводе с греческого все вместе они означают: ζῷον — животное, живое + πράξις — деятельность, движение + σκοπέω — смотр =прибор для «воспроизведения движущихся картинок». И этого события не случилось бы, не возникни пари, подтолкнувшее Мейбриджа на легендарную съёмку, в которой были задействованы всадник на скачущей по беговой дорожке лошади и «фотодром» из 12 кабин на фоне длинной белой стены, выстроенной вдоль трека.

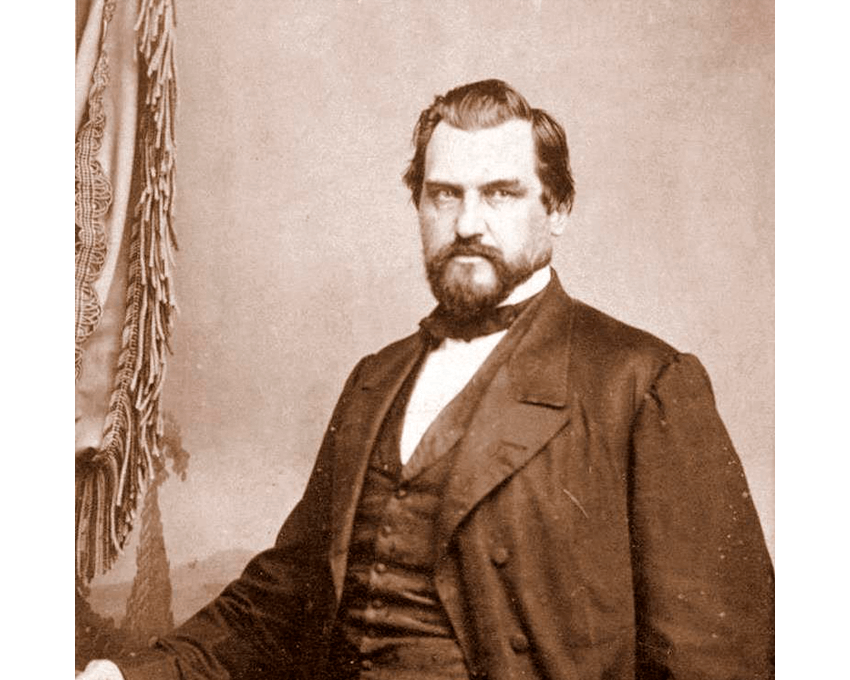

Пари на двадцать пять тысяч долларов (увы, информации о нём в подтверждённых источниках не сохранилось) заключил Леланд Стэнфорд, прежде губернатор Калифорнии, а также один из четырёх крупнейших бизнесменов в Сакраменто, известных в народе как «Большая четвёрка». Учредитель железнодорожной империи, филантроп и основатель Стэнфордского университета, он слыл страстным коннозаводчиком. Его, как и всех любителей скачек того времени, волновал широко обсуждаемый вопрос: существуют ли такие моменты, когда лошадь в галопе одновременно отрывает от земли все четыре копыта? Дело в том, что человеческий глаз не мог зафиксировать этот момент из-за скорости, с которой двигается животное, ну а художники, которые тоже не могли этого увидеть, всегда изображали бегущую лошадь как минимум с одной ногой, касающейся поверхности.

Пари на двадцать пять тысяч долларов (увы, информации о нём в подтверждённых источниках не сохранилось) заключил Леланд Стэнфорд, прежде губернатор Калифорнии, а также один из четырёх крупнейших бизнесменов в Сакраменто, известных в народе как «Большая четвёрка». Учредитель железнодорожной империи, филантроп и основатель Стэнфордского университета, он слыл страстным коннозаводчиком. Его, как и всех любителей скачек того времени, волновал широко обсуждаемый вопрос: существуют ли такие моменты, когда лошадь в галопе одновременно отрывает от земли все четыре копыта? Дело в том, что человеческий глаз не мог зафиксировать этот момент из-за скорости, с которой двигается животное, ну а художники, которые тоже не могли этого увидеть, всегда изображали бегущую лошадь как минимум с одной ногой, касающейся поверхности.  Leland Stanford

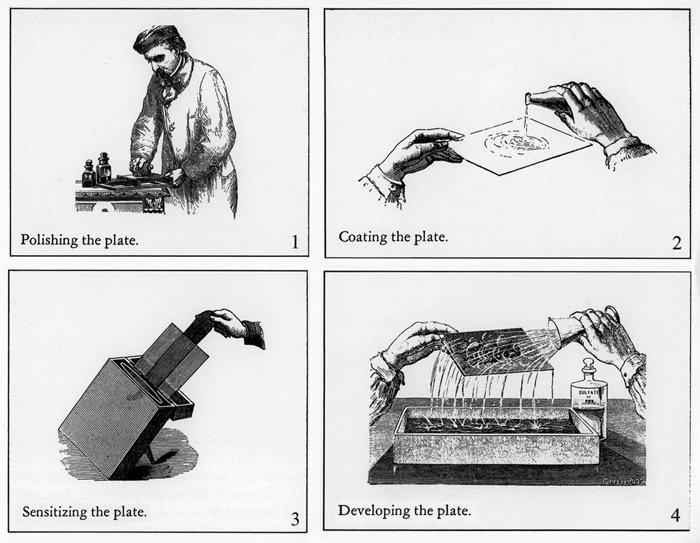

Leland Stanford В результате Стэндфорд пригласил эксцентричного англичанина, чтобы раз и навсегда рассеять сомнения на этот счёт. Мейбридж применил трудоёмкий мокрый коллодионный процесс, при котором требовалось немедленно экспонировать приготовленные эмульсионные фотопластинки, терявшие свои свойства при высыхании. В отличие от сухих пластин и дагеротипа мокрые пластины обладали высокой светочувствительностью, что позволяло работать на коротких выдержках. Подготовка к эксперименту продлилась довольно долго: исследовательская группа, которую возглавил фотограф, была собрана ещё в 1872-м – но наиболее значимые итоги были получены 19 июня 1878 года. Причиной тому были препоны не только технического, но и личного характера – вспыльчивый Мейбридж был осуждён (но, важно отметить, оправдан судом присяжных) и потому на несколько лет покинул страну.

Хотя самые первые снимки доказывали правоту Стэндфорда, тогда публика заподозрила его группу в фальсификации, склонившись к мнению, что удачный кадр был отретуширован с выгодой для заказчика. Шесть лет спустя серия снимков провелась вновь – на этот раз на глазах у гостей и представителей прессы. Мейбридж публично обработал все двенадцать пластин и ещё сырыми выложил для осмотра. На втором и третьем кадрах четыре ноги кобылы по имени Салли Гарднер не опирались на землю. Годом позже благодаря тому же Мейбриджу на свет появился зоопраксископ – одна из самых известных докинематографических технологий.

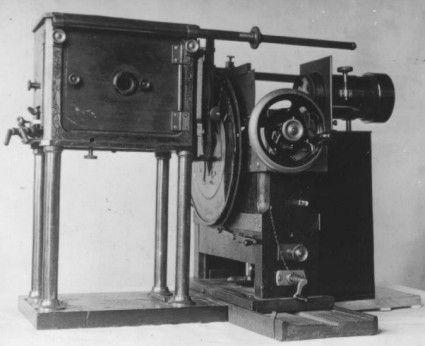

Зоопраксископ в миниатюре

Анимационные детали часов всегда являлись демонстрацией вершины мастерства. Крайне редко они встречаются сегодня в часах-автоматонах, где движущиеся элементы циферблата дублируют (или сами являются) элементами индикации. Чаще – в репетирах, часах с механизмом боя. В таком случае они называются жакемары. Их движения сопровождают звуковой сигнал, отмечающий текущий час. Исследуя эту область, российский мастер обнаружил, что до него никто всерьёз не брался за тему мультипликации, а значит, в этой нише он будет первым в мире разработчиком, внедрившим конструкцию такого типа в механический калибр. Самым логичным было взять знаменитое изображение галопирующей лошади со всадником и «оживить» его на циферблате. Но как это сделать? – В прямом смысле слова переизобрести зоопраксископ таким образом, чтобы он поместился в корпус с размерами 47,6×37,6×13,8 мм.

Зоопраксископ, по сути, является ранним проекционным аппаратом. Поэтому именно на нём базируется первый в истории синематографа кинетоскоп. Если в аппарате Мейбриджа проигрывались 40-сантиметровые стеклянные диски, диаметр соответствующего колеса в часах Чайкина составляет микроскопические, по сравнению с оригиналом, 32 мм. «Сложность задачи была для меня очевидной, — вспоминает изобретатель. — Поэтому, предвидя всякие проблемы и ловушки, я решил осаждать крепость по науке, то есть поэтапно, по заранее просчитанному плану. Сначала я построил макет механизма анимации в пластике — в увеличенном масштабе, потом в металле — в масштабе один к одному, только после этого я сделал прототип с часовым механизмом».

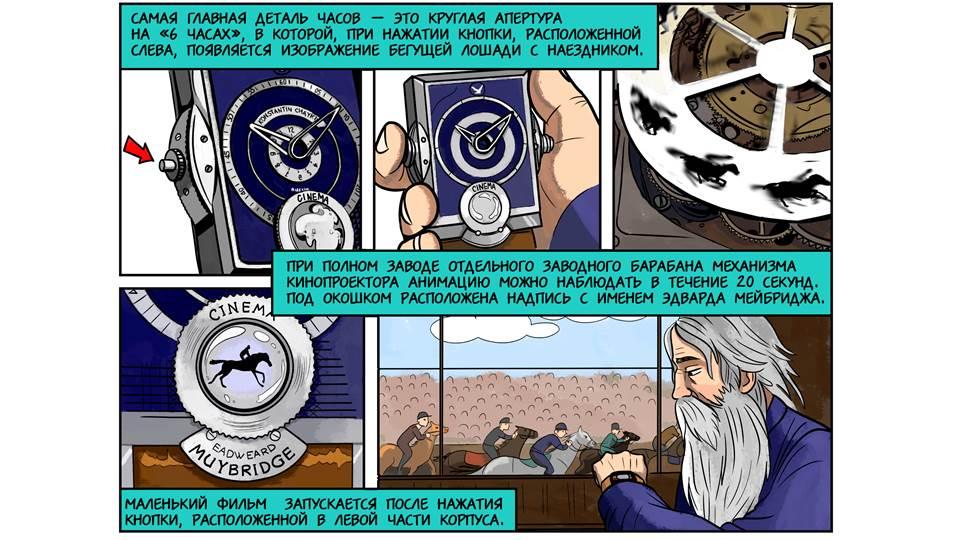

Автору было необходимо упорядочить скорость вращающегося диска – основы будущей циферблатной анимации. Для этих целей он поначалу решил прибегнуть к аэродинамическому стабилизатору, но ход работ показал, что будет достаточно стандартного триба с парой накладных камней. Конструируя инновационный модуль, Чайкин также задействовал несколько технических решений, использовавшихся на заре киноиндустрии: женевский привод (как раз заимствованный из часового дела), а также обтюратор – механизм для перекрывания потока света или иного излучения в оптических приборах. Мастер рассчитал и изготовил специальный окуляр, установив последний в нижней части циферблата: при активации специальной кнопки в нём циклически воспроизводится 12-кадровая съёмка Мейбриджа «Салли Гарднер в галопе».

На этом изящные конструкционные решения мануфактурного калибра K.06-0 с ручным заводом отнюдь не заканчиваются. Например, устройство анимации было интегрировано в него с собственным заводным барабаном: по итогу в калибре их два – один задействован для модуля (располагается внизу), второй, вверху, отвечает за ход минутной и часовой стрелок. Темп действия зоопраксископа Чайкина весьма высок для классической часовой техники: кадр длится примерно 0,08 секунды, с такой же скоростью работает и обтюратор, что примерно вдвое превышает темп колебаний баланса. Запас хода зоопраксископа 20 секунд, длительность одного полного цикла анимации из 12 кадров составляет 1 секунду.

Что касается внешнего вида и фактуры – для прямоугольного корпуса ультралимитированной серии, задуманной в количестве 12 экземпляров, было использовано белое золото. Кстати, сама модель выполнена и отделана в стиле винтажной кино- и фототехники – ещё одна отсылка к реализованной в них задумке. На это намекает не только характерная чёрно-серебристая гамма, но и отдельные элементы оформления: миниатюрный окуляр, стилизованный под объектив, заводная головка и кнопка запуска анимации, напоминающие кнопки фотоаппарата, а также центральные стрелки, вторящие форме рычажков взвода затвора и перемотки плёнки.

Задняя крышка часов, разумеется, была выполнена из сапфирового стекла, чтобы не скрывать от взгляда филигранную отделку прямоугольного мануфактурного калибра с 45-часовым запасом хода. Циферблат, покрытый чёрным лаком, не менее искусно гильоширован традиционным узором «Парижские гвозди».

Часы впервые были показаны публике в Москве 9 апреля 2013 года – а буквально через две недели произвели фурор на Базельской выставке, в те годы являвшейся одной из крупнейших международных профессиональных экспозиции.

О модели написали все ведущие порталы, следящие за новостной повесткой хронометрической индустрии. Майкл Клеризо, колумнист The Wall Street Journal, в интервью для сайта thewatches.tv отметил, что включает её в пятёрку лучших часов выставки.

Ну а о креативности автора Cinema можно судить не только по, собственно, изобретению, но и тому, какими методами информацию о нём доносили аудитории. В конце концов, никто из заслуженных швейцарских мэтров прежде (да и потом тоже) не прибегал к жанру комикса, чтобы рассказать на его страницах о разработанных своими силами наручных часах.

Часы Cinema, наделённые небывалой эмпатией, и реакция, которую они вызывали у зрителей, заставили задуматься Константина о том, какую огромную роль играют неподдельные эмоции. Именно они стали прологом к появлению родоначальника обширного семейства «ристмонов» – знаменитому улыбающемуся «Джокеру» с циферблатом, наделённым антропоморфным дизайном. Подробности этой истории можно узнать в книге «Константин Чайкин: высокое часовое искусство с российской душой». В ней можно найти детальную биографию часовщика, все этапы его творческого пути, а также интересные истории из внутренней кухни создания часовых шедевров автора. Приобрести книгу можно через Озон.