Первыми часами, сконструированными и полностью изготовленными Константином Чайкиным, были настольные часы «Основополагающий турбийон». Этим проектом он занимался в конце 2003-го и первой половине 2004-го, а по его окончании приступил к разработке снова настольных часов, как сложных с турбийоном и календарными функциями, так и относительно простых, только с турбийоном. Были несколько попыток поработать с наручными часами, в основном, по частным заказам, однако, их можно рассматривать лишь как пробу сил в этом направлении часового дела.

Впервые серьёзно о наручных часах собственного производства Чайкин задумался в 2007 году. Помог, как это часто бывает, случай. C 16 по 19 октября в Москве проходила выставка «Московский часовой салон», куда Константин привёз несколько экземпляров заново разработанных им небольших настольных турбийонов, в том числе и «Муравьиный турбийон» с прозрачными сапфировыми мостами (стоит отметить, что это первые в мире настольные часы на сапфировых мостах и наиболее компактные настольные часы с турбийоном), а также вторые пасхальные часы. Вместе с часами настольными мастер привёз на выставку макетный прототип наручного вечного календаря с индикацией даты православной Пасхи. Однако дальше макета дело не пошло, проект наручной пасхалии так и не был реализован, так как и разработка, и изготовление сверхсложных наручных часов подобного рода потребовала бы значительных средств. Тем не менее, участие в выставке дало ему другой шанс.

2007 год. Макетный прототип наручного вечного календаря с индикацией даты православной Пасхи Константина Чайкина.

2007 год. Макетный прототип наручного вечного календаря с индикацией даты православной Пасхи Константина Чайкина. Герман Полосин, коллекционер и специалист по реставрации старинных часов, познакомил Константина с Ильёй Гельфманом, начинающим коллекционером, который загорелся идеей организовать в России производство высококлассных механических часов. Понятно, что Чайкин с его способностью не только изготовить сложную часовую механику, но также сконструировать механизмы и изобрести свои собственные сложные функции был перспективным партнёром для Гельфмана. На выставку тот пришёл с вполне конкретной идеей, которую ему подсказали недавно приобретённые им с подачи Полосина старинные карманные часы «Мистерия» фирмы «Арман Швоб» (Armand Schwob & Frère Mystérieuse) примерно 1890 года, сработанные в Ла-Шо-де-Фоне. Гельфману представлялись наручные часы с таинственной системой индикации времени, но без центральной металлической оси, имевшейся в прозрачном циферблате часов «Арман Швоб».

Карманные часы Mystérieuse фирмы Armand Schwob & Frère примерно 1890 года. Фото – Antiquorum.

Карманные часы Mystérieuse фирмы Armand Schwob & Frère примерно 1890 года. Фото – Antiquorum. Здесь следует отметить, что с точки зрения соответствия исполнения идее «таинственных» часов с прозрачным циферблатом к часам «Мистерия» фирмы «Арман Швоб» имеются претензии. Циферблат в часах этой марки был далеко не столь прозрачным, как того хотелось бы. В его центре имеется звёздчатый или цветочный декор, призванный замаскировать миниатюрную вексельную передачу, которая используется для привода часовой стрелки, периферия перенасыщена часовыми маркерами в виде арабских или римских цифр, также имеется минутная шкала с дополнительной пятиминутной разметкой арабскими цифрами.

Созданная Чайкиным объёмная модель механизма часов «Мистерия 1000 камней».

Созданная Чайкиным объёмная модель механизма часов «Мистерия 1000 камней». Константин Чайкин загорелся идеей, тем более что ему представилась возможность придумать свой вариант классической конструкции – в формате наручных часов. Он сделал проект значительно более сложным, добавив в него построенные на том же принципе «таинственной» индикации планисферу с картой звёздного неба над Санкт-Петербургом и годовой календарь. «Таинственные» индикаторы были дополнены обычными, то есть непрозрачными указателями фазы Луны, уравнения времени и запаса хода. И да, он ликвидировал в часах ту самую центральную металлическую ось, раздражавшую Гельфмана. Чтобы сделать это, он решил установить вращающиеся сапфировые диски прозрачного циферблата на изготовленные им самим периферийные шарикоподшипники, где шариками были миниатюрные сферические рубиновые камни. Всего в окончательном варианте часов было 1020 камней, из них 954 камня «таинственного» указателя и 66 обычных камней механизма. Отсюда, кстати, произошло название часов: «Мистерия 1000 камней».

«Мистерия 1000 камней».

«Мистерия 1000 камней». Единственный доведённый до окончательного вида экземпляр «Мистерии 1000 камней» ждала печальная судьба – часы были украдены из гостиничного номера. Илья Гельфман вспоминает: «В апреле 2009-го аукционный дом „Cотбис“ устроил в Лувре благотворительный бал и выставку, там я собирался представить эти часы. Но я не смог, в последний момент отменил, вместо меня полетела моя подруга. Всё прошло, как планировалось – бал, ужин, презентация. Она пришла в номер в час ночи, положила часы на стол, легла спать, а когда утром – часов в десять – проснулась, часов уже не было. Подняли записи всех камер, ничего не нашли – в общем, похоже, кто-то воспользовался карточкой отеля, зашёл в номер, забрал часы и вышел. Месяца через три нам прислали сообщение, предлагали купить часы за 25 тысяч евро. Конечно, мы обратились в полицию, но в итоге они ничего не нашли, и больше этих часов никто не видел».

«Мистерия 1000 камней», вид с оборотной стороны.

«Мистерия 1000 камней», вид с оборотной стороны. Таинственное исчезновение «таинственных» часов – казалось бы, это печальное событие должно остаться единственным в истории часового дела. Представьте себе моё удивление, когда в тексте статьи «Первые прозрачные [карманные] часы» Хуана Ф. Дениса (Juan F. Déniz – The first transparent watch), которая была напечатана в журнале Antiquarian Horology в 2018 году, я обнаружил упоминание о факте кражи «таинственных» часов на Всемирной выставке 1889 года, проходившей Париже с 6 мая по 31 октября. Снова таинственное исчезновение «таинственных» часов, и опять в Париже! Я погрузился в изучение подшивок парижских газет того года и наконец обнаружил искомое. 1 ноября 1889 года, то есть уже на следующий день после официального закрытия выставки, парижская газета Le Temps в номере 10405 в статье «Хроника выставки: различные новости» сообщала (в переводе с французского): «Вчера было обнаружено, что ценные часы, называемые „таинственными“ по причине особенной конструкции их механизма, исчезли из витрины [коллективной выставки лучших часов французских фирм], тогда как замок остался неповреждённым. Представителем потерпевшей фирмы была немедленно подана жалоба касательно таинственной кражи»…

Le Temps, номер 10405, текст о таинственной пропаже «таинственных часов» выделен автором.

Le Temps, номер 10405, текст о таинственной пропаже «таинственных часов» выделен автором. Вы всё ещё считаете, что таинственных совпадений не бывает?

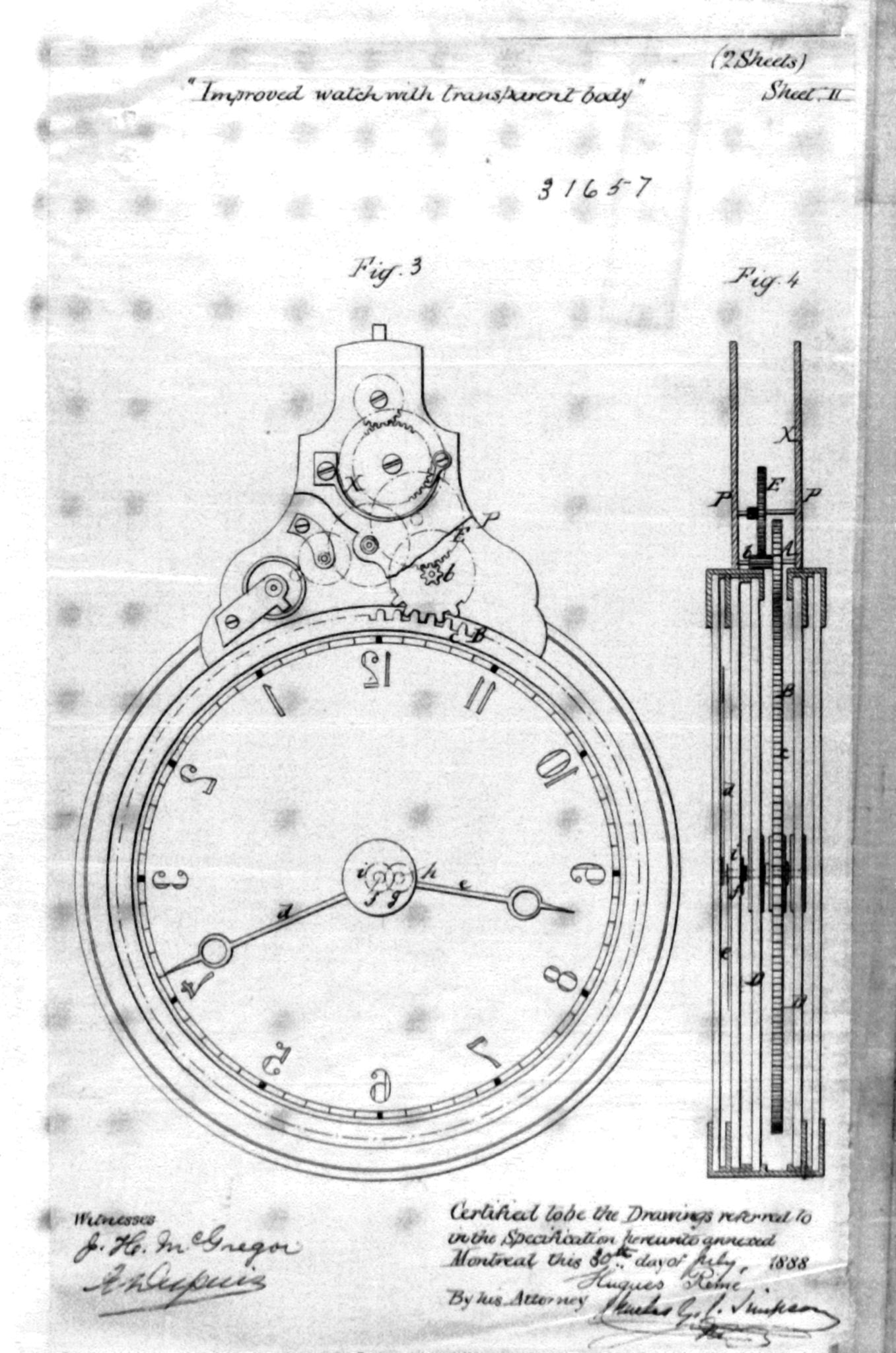

Иллюстрация из канадского патента Юга Рима.

Иллюстрация из канадского патента Юга Рима. P.S. Идея «таинственных» часов неоднократно реализовывалась различными часовщиками и часовыми фирмами, в частности, в карманных часах «таинственная» индикация времени была впервые применена фирмой Armand Schwob et Frères, основанной братьями Арманом и Авраамом Швобами в Париже. Часы производились по патенту французского часовщика Юга Рима (Hugues Rime) с 1888 по 1892 годы, скорее всего, в Швейцарии, в городе Ла-Шо-де-Фон, где у Armand Schwob et Frères был представительский офис. В 1892 году фирма Armand Schwob et Frères обанкротилась. Как следует из имеющейся на часах и их механизмах нумерации, было, по-видимому, изготовлено всего несколько тысяч экземпляров, скорее всего, не более трёх тысяч. В механизме часов использовались компоненты калибров женских карманных часов (часов-подвесок) на цилиндровом ходу: главная передача, заводной барабан и заводная передача, узел хода.